ASEAN Ban Falls Short in Pressuring Myanmar Junta

Myanmar regime not invited to ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur but the bloc must change tack if it really wants to effect change

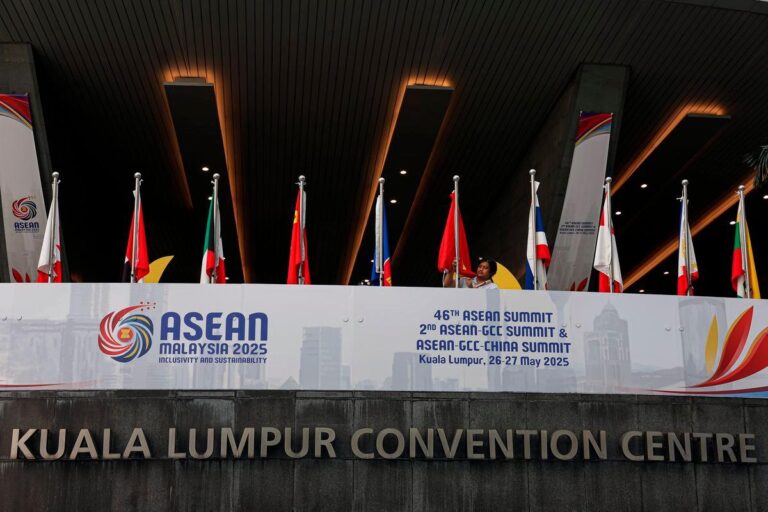

Myanmar’s junta has once again been excluded from a high-level Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit, this time the event to be held in Kuala Lumpur from May 26-27. This has become a de facto policy tool for the bloc since the February 2021 democracy-suspending military coup.

Yet the central question remains: Is this diplomatic isolation enough to influence the junta’s behavior, or does it risk pushing the country, and its people, into deeper political and civil alienation?

The answer lies in understanding three dimensions: the effect of isolation, the price of exclusion and the unintended alienation that such a move can bring—not just to the regime but to the people who are already resisting it.

ASEAN’s decision to bar the junta, known as the State Administration Council, from summits unless it makes “meaningful progress” on the Five-Point Consensus was historic.

It signaled a departure from ASEAN’s long-standing principle of non-interference in members’ internal affairs, making it perhaps the first serious attempt to hold a member accountable for gross human rights violations.

Symbolically, this has tarnished the junta’s desire for legitimacy. Regional isolation—particularly when reinforced by exclusion from summits with the Gulf Cooperation Council, China, the EU and the US—hurts the military’s claim to be the rightful representative of Myanmar.

The junta is thus widely seen not just as illegitimate but as diplomatically untouchable. For military regimes that thrive on hierarchical recognition, this is a significant and stinging reputational blow.

However, the effect remains limited in material terms. The junta continues to control major cities, key infrastructure and the levers of coercive power in Myanmar. And it’s winning the war, at least in the air, by pummelling ethnic armies and civilian populations in areas they control to stall their territorial advances.

The junta has alternative partners in Russia and China, both of whom prioritize strategic interests over normative pressure. In the absence of sufficient economic or military consequences, exclusion and sanctions haven’t been enough to undermine the junta.

Exclusion has provided space for the National Unity Government (NUG)—the civilian opposition in exile composed of many members of the toppled National League for Democracy-led (NLD) government—to gain international recognition, particularly among democratic countries.

For the NUG, the junta’s absence from summits means fewer opportunities for Naypyidaw to manipulate ASEAN processes or to masquerade as a legitimate voice for Myanmar.

The NUG has engaged with sympathetic ASEAN states such as Malaysia and Indonesia on the sidelines, and its representatives have appeared in informal dialogues and Track 2 diplomacy efforts. This parallel diplomacy weakens the junta’s wished-for monopoly on representation.

However, ASEAN has not extended formal recognition to the NUG, which limits how far the opposition can leverage the junta’s exclusion. The policy of “non-recognition” without active support leaves both the junta and the NUG in diplomatic limbo.

The risk of exclusion without deeper engagement is that Myanmar’s population becomes more alienated from ASEAN. This includes not only ethnic minority groups but also the growing youth-led resistance movements that see ASEAN as ineffectual and, at times, complicit through inaction.

The perception that ASEAN is “sidelining” Myanmar rather than working for its people could create long-term reputational damage to the bloc. Civil society actors and diaspora groups have already begun looking elsewhere—for example, to the UN, Western governments or global human rights organizations—for solidarity and advocacy.

This alienation deepens the strategic dilemma: ASEAN cannot bring Myanmar back into the fold without appearing to reward impunity, but continued exclusion leaves narrow, if any, pathways for re-integration or healing.

The longer this persists, the more Myanmar drifts from the regional family. Thus important steps have to be taken.

For one, ASEAN has to institutionalize Track 2 Diplomacy to keep the momentum moving. Just as importantly, ASEAN should work with credible academic and civil society groups to maintain dialogues with both NUG and ethnic organizations. This must be seen as a commitment to Myanmar’s people, not the regime.

Alternatively, ASEAN could allow conditional engagement. This implies allowing Myanmar back into technical meetings, but only if verifiable humanitarian access to conflict zones is granted. ASEAN-led monitoring mechanisms would be required to enforce such an arrangement.

Beyond the above, engaging with China, India and even Russia is now a must. ASEAN must quietly coordinate with Myanmar’s two largest neighbors, as well as one of its biggest backers, namely Russia, to exert maximum leverage and enforce consequences while offering credible off-ramps for conflict de-escalation.

Just as importantly, instead of relying only on the UN Special Envoy to Myanmar, ASEAN should appoint a special envoy of its own. That person should carry a clear mandate to amplify the voices of ordinary Myanmar citizens, not just to engage the military.

Excluding the junta from ASEAN summits is a moral stance—and arguably a necessary one. But on its own, exclusion is not enough to change the junta’s behavior. ASEAN must complement this approach with structured engagement with all involved – the junta, the opposition and, most importantly, Myanmar’s people.

Otherwise, Myanmar risks becoming a permanently estranged state with a regime that outlasts the region’s patience and its people’s hope for change.

Thank you for reading! Visit us anytime at Myanmar.com for more insights and updates about Myanmar

Related posts:

Inle Lake Buddhist Festival in Myanmar | Tradition & Renewal

Inle Lake Buddhist Festival in Myanmar | Tradition & Renewal

Thailand Extradites Shwe Kokko Tycoon She Zhijiang to China

Thailand Extradites Shwe Kokko Tycoon She Zhijiang to China

Myanmar’s earthquake death toll rises to 3,770

Myanmar’s earthquake death toll rises to 3,770

Myanmar Military Paraglider Strike Kills Dozens

Myanmar Military Paraglider Strike Kills Dozens

ASEAN Rejects Myanmar’s Military Elections, Illegitimate

ASEAN Rejects Myanmar’s Military Elections, Illegitimate

U.S. Identifies Myanmar and Other Nations in Annual Drug Report

U.S. Identifies Myanmar and Other Nations in Annual Drug Report