Introduction to Myanmar Theravada Buddhism

Theravada Buddhism is the dominant religious tradition in Myanmar and has shaped the country’s cultural, social, and intellectual life for many centuries. More than 85 percent of the population identify as Buddhist, and the vast majority follow the Theravada school, which emphasizes personal discipline, moral conduct, and the pursuit of enlightenment through insight and meditation. Monasteries, pagodas, and Buddhist rituals are woven into daily life, influencing social norms, family customs, holidays, and community organization.

Buddhism in Myanmar is not confined to private belief or occasional worship but functions as a visible and continuous presence in public space. Monks collect alms each morning, festival days are integrated into the national calendar, and children are commonly introduced to Buddhist teachings from a young age. The religion provides a moral framework and a vocabulary for discussing ethical behavior, duty, generosity, and social responsibility.

Theravada doctrine arrived in Myanmar through historical interactions with South Asia and Sri Lanka, and over time it developed distinct Burmese characteristics in architecture, ritual observance, and monastic organization. Although Myanmar shares many core elements with other Theravada countries such as Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, its liturgy, calendar, and social expressions of devotion have a uniquely Burmese identity.

Section 2 — Historical Development of Buddhism in Myanmar

The spread of Buddhism in Myanmar is a gradual historical process shaped by migration, trade, royal patronage, and monastic exchanges with Sri Lanka and India. While the precise date of its first arrival is debated, inscriptions and chronicles suggest that Buddhism has been present in the region for more than 1,500 years.

Early Introduction and Pyu Kingdoms

Evidence from Chinese records and archaeological findings indicates that the Pyu city-states in Upper Myanmar practiced Buddhist rituals as early as the first millennium CE. Excavations at sites such as Sri Ksetra and Beikthano show Buddhist stupas, inscriptions, and iconography linking the Pyu to early Buddhist devotional culture.

Bagan Period (11th–13th Century): Consolidation

A decisive moment in the history of Burmese Buddhism came in the 11th century under King Anawrahta of Bagan. According to Burmese chronicles, Anawrahta converted to Theravada Buddhism and sought religious legitimacy by obtaining scriptures and relics from Sri Lanka. This royal endorsement led to:

Establishment of state patronage for monasteries

Suppression of competing sects and local cults

Construction of large-scale pagodas and temples

Standardization of religious practice and scriptural study

The Bagan era left a lasting architectural and intellectual legacy in thousands of temples that still stand on the Bagan plain.

Post-Bagan Transmission and Monastic Reforms

After the fall of Bagan, various Burmese kingdoms continued to patronize the sangha (the community of monks). Religious connections with Sri Lanka remained active, especially during periods when reforms were needed to address perceived laxity in monastic discipline. These periodic reforms reinforced:

Strict adherence to the Vinaya (monastic code)

Unified ordination lineage

Textual learning and scriptural preservation

Continuity into the Modern Era

Despite political changes, colonial rule, and modernization in the 19th–20th centuries, Theravada Buddhism remained continuous in its institutions and teaching. Monasteries functioned as centers not only of religion but also of literacy, community education, and cultural identity.

Section 3 — The Monastic Order and Its Role in Daily Life

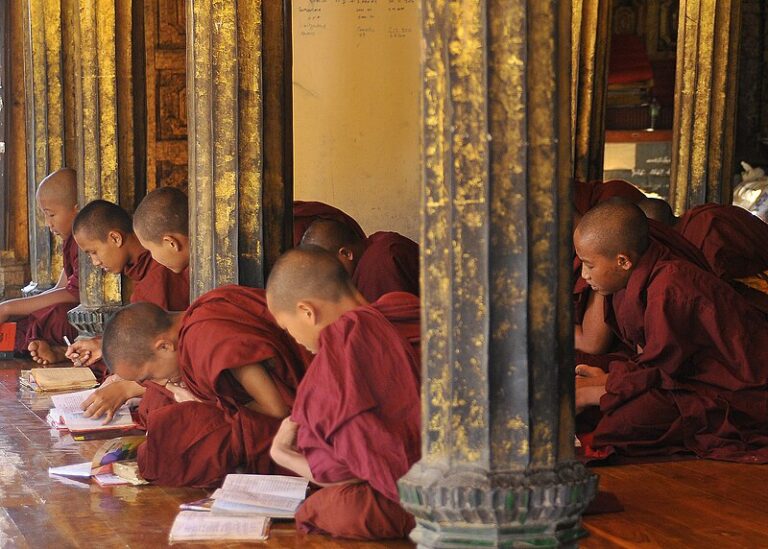

The monastic community is the most visible institution in Myanmar Buddhism. Monks and novices live according to strict ethical rules, dedicate themselves to study and meditation, and serve as models of moral conduct for the lay population. Monasteries exist in every town and almost every village, making religious life geographically accessible to ordinary people.

Ordination and Monastic Life

Joining the monastic order can be permanent or temporary. Many boys in Myanmar enter a monastery for a short period during childhood or adolescence as a cultural rite of passage. Permanent monks commit to a full life of renunciation, guided by rules that regulate diet, dress, communication, possessions, and social interaction.

Typical monastic discipline emphasizes:

Celibacy and renunciation of family life

Simplicity in dress, usually a saffron or maroon robe

Avoidance of entertainment, luxury, and trade

Restraint in speech and behavior

Focus on study, memorization, and meditation

Monks depend entirely on lay generosity for food, medicine, and basic needs. Each morning, monks walk silently through neighborhoods accepting offerings of cooked rice and other essentials. This exchange of material support and religious merit reinforces mutual dependence between lay society and the monastery.

Monasteries as Centers of Learning and Community

Beyond religious training, monasteries historically functioned as schools for reading, writing, and moral instruction. Even today:

Many children attend monastery-based classrooms before public schooling

Adults visit monks for advice on ethical and personal matters

Religious sermons accompany major life events (birth, marriage, death)

The presence of monasteries gives Buddhism a structural role in community life that extends beyond worship.

Section 4 — Core Beliefs and Ethical Practices in Burmese Buddhism

Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar emphasizes personal ethical discipline, mental cultivation, and the gradual accumulation of merit as a path toward liberation from suffering. While advanced philosophical interpretations exist, the everyday practice of Buddhism among laypeople is guided mainly by a set of core concepts that shape behavior, social obligations, and religious observance.

Belief in Cause and Effect (Karmic Consequences)

A foundational idea in Burmese Buddhism is that intentional actions — good or bad — inevitably produce corresponding results, either in this life or in future lives. This belief has direct social effects:

People expect that moral behavior brings later benefit and immoral actions lead to harm

Acts of generosity, honesty, and compassion are seen as spiritually profitable

Misfortune is often explained not as random but as a result of past actions

This view does not encourage fatalism but motivates ethical living. Instead of relying on external divine punishment or reward, Burmese Buddhists view ethical accountability as an internal and automatic process.

The Pursuit of Merit through Giving and Good Conduct

Merit is the positive spiritual value generated by generous and virtuous actions. In Myanmar, acquiring merit is a major part of religious life. Common ways of earning merit include:

Offering food and material support to monks

Funding the construction or repair of a pagoda or monastery

Releasing animals from captivity (such as fish or birds)

Observing ethical precepts on religious days

Sponsoring communal meals, festivals, or religious events

Merit is often shared symbolically with deceased relatives or with all beings, reinforcing the idea that good actions benefit more than the individual.

Meditation and Mental Discipline

Although not all laypeople practice meditation regularly, meditation is recognized as a central path in Buddhism. Monasteries and retreat centers provide instruction in mental training aimed at:

Developing concentration and calm

Observing thoughts and emotions without attachment

Recognizing the impermanent and unsatisfactory nature of experience

Those who practice believe it reduces anxiety, improves clarity, and gradually weakens unwholesome mental habits.

Moral Precepts as Ethical Framework

Lay Buddhists frequently follow a set of ethical guidelines that prohibit harmful behavior. On ordinary days most uphold five basic rules, while stricter observance may be undertaken on religious holidays or during retreats. These rules structure ethical life by discouraging violence, theft, deception, sexual misconduct, and intoxicant use. Observance is considered both a personal duty and a way of maintaining dignity and social trust.

Section 5 — Rituals, Religious Observance, and Daily Devotion

Burmese Buddhism is not limited to monastic life; it is actively expressed through daily gestures of respect, periodic observance, household rituals, and large communal celebrations. These practices create a rhythm of religious engagement that ties individuals and communities to the Buddhist tradition throughout the year.

Daily Acts of Devotion

For many Burmese Buddhists, religious activity begins at home. Families often maintain a small shrine with an image of the Buddha where offerings of flowers, candles, or incense are made. Typical daily practices include:

Bowing or placing hands together before the Buddha image

Reciting simple verses of homage or moral reflection

Making mental resolve to act with restraint and kindness that day

These actions reinforce humility, mindfulness, and moral intention before entering daily tasks.

Visiting Pagodas and Monasteries

Pagodas and monasteries are central spaces for public worship and reflection. Visits are common on weekends, religious holidays, and at important moments in life such as examinations, business openings, or travel departures. Visitors:

Walk around the pagoda in respectful silence

Light candles and offer flowers

Sit quietly in reflection or listen to a sermon

Place donations in boxes to support religious maintenance

These visits are not dependent on fixed schedules; they are integrated into ordinary social life.

Religious Festivals and Annual Observance

Myanmar’s calendar includes numerous Buddhist festivals that structure community life and reinforce religious identity. Some of the most prominent include:

Thingyan (Water Festival) — marking the Buddhist New Year with symbolic cleansing, generosity, and communal celebration

Waso (Beginning of Monks’ Rain Retreat) — when many youths temporarily ordain and the community increases donations to monasteries

Thadingyut (Festival of Lights) — expressing gratitude to elders and teachers through gifts and acts of respect

Tazaungdaing — marked by communal offering of robes to monasteries and lantern-lit ceremonies

Festivals combine devotion with social participation. They reinforce family bonds, strengthen community identity, and reassert the link between religious observance and cultural life.

Merit-Making Ceremonies and Social Obligations

Special ceremonies are held throughout the year to mark life transitions — births, memorials, ordinations, and house blessings. These events normally include:

Inviting monks to chant and receive offerings

Providing meals for attendees and the monastic community

Sharing merit with deceased relatives or with all beings

By hosting such ceremonies, families both fulfill religious duty and express social generosity.

Section 6 — Architecture, Symbols, and Material Expressions of Buddhism in Myanmar

Religious architecture is one of the most visible expressions of Buddhism in Myanmar. From monumental pagodas to small roadside shrines, built space reflects devotion, historical continuity, and cultural identity. The visual landscape is dominated by gold-covered domes, whitewashed stupas, carved wooden monasteries, and stone Buddha images that function as both religious objects and cultural symbols.

Pagodas and Stupas

Pagodas — often towering and gilded — are the most recognized Buddhist structures in Myanmar. They typically enshrine relics, sacred texts, or symbolic offerings and serve as focal points for worship and pilgrimage. Notable features include:

Bell-shaped dome symbolizing the universe

Finial spire often decorated with precious metals and jewels

Circular walkways for ritual circumambulation

The most famous example is the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, regarded as the spiritual heart of the country. Its gold-plated surface and jeweled ornamentation embody both religious reverence and national heritage.

Temples and Monastic Compounds

Temples contain images for contemplation and halls for teaching. Monasteries often include:

Residential quarters for monks

Libraries of religious texts

Halls for sermons and chanting

Courtyards for processions and public ceremonies

These spaces are functional as well as symbolic, providing education, shelter, and ritual order to the community.

Buddha Images and Iconography

Images of the Buddha appear in stone, bronze, wood, lacquer, and marble. They are not worshiped as divine beings but serve as visual aids for reflection on calmness, purity, and compassion. Variations in posture — seated, standing, reclining — correspond to episodes in the Buddha’s life and carry interpretive meaning for viewers.

Relics and Sacred Objects

Certain pagodas are believed to contain bodily relics or items associated with the Buddha. While the doctrinal importance lies in their symbolic value rather than the physical material, relics act as focal points for devotion, pilgrimage, and ritual commemoration.

Section 7 — Social Role, Family Life, and Cultural Integration

Buddhism in Myanmar functions not only as a system of belief but as a social framework that shapes family relationships, community obligations, and major life events. Religious values inform how people speak, make decisions, handle conflict, and commemorate transitions across the life cycle.

Influence on Family and Daily Conduct

Even in non-ritual contexts, Buddhist principles guide behavior inside households:

Children are taught to speak gently and respect elders

Conflict is discouraged through patience and restraint

Acts of generosity to monks and neighbors are treated as family responsibilities

Moral stories from scripture are used to teach humility and gratitude

The home, the school, and the monastery reinforce the same ethical vocabulary, making Buddhism part of social upbringing rather than a private philosophical choice.

Life-Cycle Rituals

Buddhist customs accompany critical stages of life. Although not required by doctrine, these practices serve cultural and ethical purposes.

Birth and Early Childhood

Families often invite monks to chant blessings for the newborn’s wellbeing. Later, a child’s first haircut or ear-piercing may be accompanied by a visit to a pagoda and donations for merit.

Childhood Ordination

Many boys undergo temporary ordination during youth, wearing robes and living briefly in a monastery. This rite marks moral initiation, teaches self-discipline, and allows the family to earn social respect through religious participation.

Marriage

Marriage is a social contract rather than a religious sacrament in Buddhism, yet it is often framed with Buddhist etiquette. Couples may visit a pagoda or invite monks to bless the union indirectly by chanting (monks do not officiate weddings themselves). The emphasis is placed on mutual respect, ethical conduct, and responsible family life.

Funerals and Memorial Rituals

Death is treated as a natural transition affected by moral causes. Funerals typically include:

Monks chanting passages that remind listeners of impermanence

Relatives preparing food and donations for merit on behalf of the deceased

Sharing merit verbally and dedicating the moral benefit to the departed

Subsequent anniversaries or merit-making meals may be held to honor the memory and reinforce community ties.

Collective Identity and Public Morality

Buddhism also supports shared standards of public behavior:

Cheating, aggression, and dishonesty are stigmatized as spiritually harmful

Generous donors gain not only merit but also public admiration

Community disputes are often framed in moral rather than legal terms

Because religious language is widely understood, it provides a common moral vocabulary across social classes and regions.

Section 8 — Education, Scriptural Study, and Intellectual Traditions

Buddhism has shaped educational life in Myanmar for centuries. Before the introduction of modern schooling, monasteries served as the primary institutions of literacy and learning, providing free instruction to boys from rural and urban communities alike. Even after the development of state-run schools, the intellectual tradition rooted in monasteries continues to influence how knowledge and moral values are transmitted.

Monastic Education as the Historical Foundation

For generations, monasteries taught reading, writing, memorization, and ethical instruction to children across the country. Their role extended beyond religion:

They raised literacy rates in pre-colonial and colonial eras

They served as boarding schools for poor or orphaned boys

They offered structured daily routines of discipline and study

Scriptural study required analytical skills, memory training, and debate, giving monastic education an intellectual rigor that formed the basis for scholarly culture in Myanmar.

Study of Religious Texts and Commentary

Advanced students in monasteries engage in deep study of canonical texts, commentaries, and doctrinal interpretations. This includes:

Memorization of verses for recitation

Logical analysis of ethical and philosophical arguments

Public examinations to certify levels of mastery

The highest-ranking scholars earn recognition and may become influential teachers or examiners within the monastic system.

Influence on Modern Public Education

Although secular public schools now operate nationwide, Buddhist values continue to shape educational norms in indirect ways:

Moral conduct and respect for teachers are emphasized in classrooms

School events frequently begin or end with visits to pagodas

Public holidays follow the Buddhist calendar

Donation drives and community service mirror merit-making customs

Even in university settings, ethical discussions often draw on Buddhist reasoning, reflecting the deep imprint of religious culture on intellectual life.

Lay Study and Adult Learning

Not all Buddhist study takes place within monasteries. Laypeople attend weekend sermons, read simplified explanations of doctrine, and participate in study circles that discuss ethical living and life goals. This has created a form of lifelong learning in which religion remains intellectually active beyond youth.

Section 9 — Preservation, Continuity, and Modern Adaptation

Although its core doctrines remain stable, Buddhist practice in Myanmar has adjusted to new economic conditions, urban lifestyles, and digital communication. These changes have not reduced religious relevance; instead, they have redirected how devotion and learning are expressed.

Urbanization and Changing Lifestyles

As more people move to cities and work in wage-based employment, the rhythms of religious life have adapted:

Early morning alms rounds continue even in dense urban streets

Pagoda visits now occur in evenings or weekends instead of daytime

Religious study is often pursued through recorded sermons rather than live attendance

Festivals are coordinated around work schedules without losing ceremonial character

These shifts allow Buddhist practice to maintain continuity while fitting modern routines.

Digital Religion and Media Adaptation

Technology has introduced new forms of participation:

Sermons are streamed on Facebook and YouTube

Chanting recordings are played in homes and cars

Digital calendar apps remind users of religious days

Donation platforms allow merit-making online

Laypeople now engage with Buddhist teachings without being physically present at monasteries. Digital channels extend access to audiences who travel, live abroad, or have limited mobility.

Preservation through Cultural Expectation

Even as lifestyles change, the expectation that individuals participate in religious life remains strong. Families still perform rites for life events, employers release staff on festival days, and communities maintain contributions to pagodas and monasteries. Continuity is upheld by social habit and collective identity rather than coercion or formal enforcement.

Non-Political Challenges Without Controversy

Without entering political topics, it is still possible to note neutral structural challenges:

Economic hardship can reduce donations to monasteries

Migration abroad creates distance between families and local ritual life

Younger generations may prioritize secular education over scriptural study

However, these changes have not displaced Buddhism. Instead, they encourage new formats of practice, indicating resilience rather than decline.

Section 10 — Summary and Conclusion

Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar is both a belief system and a cultural framework that extends into nearly every area of daily life. Its historical development through royal patronage, monastic scholarship, and community participation created a stable religious infrastructure that has lasted for centuries. The sangha provides moral guidance, educational functions, and symbolic leadership, while laypeople sustain monastic life through generosity and social engagement.

Religious observance is visible in household rituals, pagoda visits, seasonal festivals, life-cycle ceremonies, and ethical behavior rooted in cause and effect. Even as Myanmar modernizes, urbanizes, and connects to global technology, Buddhist practice continues to adapt without losing its public presence or cultural authority. Digital sermons, online donations, and flexible schedules reshape form but not substance. In this continuity, Buddhism remains not merely a doctrine but a living tradition embedded in family, community, and identity.

FAQ — Myanmar Theravada Buddhism

1) Why is Buddhism so widespread in Myanmar?

Buddhism became dominant through a combination of early adoption, royal sponsorship, and its integration into education and community life. Over time, monasteries shaped literacy, ethics, and social customs, making Buddhism not just a personal choice but a generational legacy embedded in family and community identity.

2) Do all Burmese people practice Buddhism in the same way?

No. While most people share the same core beliefs and rituals, individuals vary in frequency, intensity, and interpretation. Some focus on merit-making and festivals, others emphasize meditation and study, and monks follow a much stricter path. The shared framework allows diverse levels of involvement.

3) Are pagoda visits necessary to be a good Buddhist in Myanmar?

Pagoda visits are culturally important but not a doctrinal requirement. Many people visit regularly to cultivate gratitude, calmness, and generosity, but Buddhism also teaches that ethical behavior, self-discipline, and mindful living can be practiced anywhere, including at home and at work.

4) Why are monks highly respected in Myanmar society?

Monks are respected because they renounce ordinary comforts to pursue moral and spiritual training. They serve as ethical models, teach the public, preserve religious knowledge, and depend entirely on lay support. This mutual exchange encourages reverence without requiring worship of individuals.

5) Has modern life weakened Buddhist practice in Myanmar?

Modern conditions have changed the form but not the presence of Buddhist practice. People may rely on digital sermons, visit pagodas after work instead of mornings, or donate online instead of in person. These adjustments show adaptation rather than abandonment, keeping religion relevant in a new context.