Myawaddy Scam Centers

Introduction

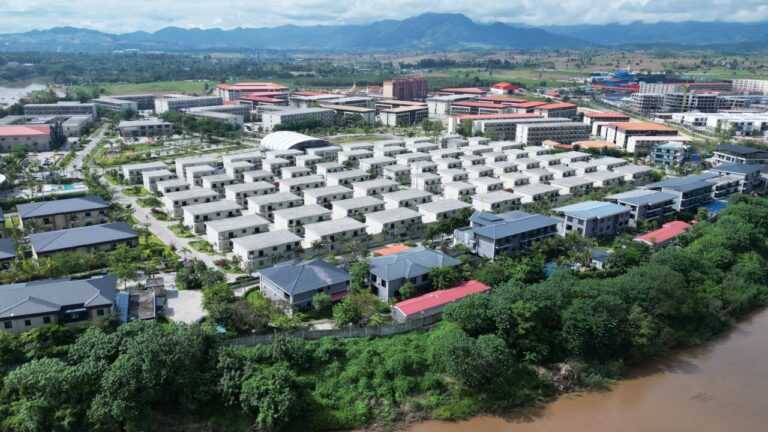

Myawaddy is a border town located in eastern Myanmar, directly opposite Mae Sot in Thailand’s Tak Province. The two towns are linked by the Thai–Myanmar Friendship Bridge, and for decades this crossing has served as a major route for cross‑border trade, migration, and informal economic activity. In recent years, however, the area has gained global attention for a different reason: the emergence of large‑scale online scam compounds operated mainly by transnational crime syndicates.

These scam centers are typically housed inside fortified compounds, guarded and isolated, where trafficked workers are forced to commit online financial fraud targeting victims worldwide. Reports by journalists, rights organizations, and Thai and Myanmar officials describe these sites as part of a wider criminal economy that took root amid Myanmar’s prolonged political instability and weak law enforcement in contested border regions.

Historical Background — How the Scam Compounds Emerged

The rise of scam compounds in and around Myawaddy can be traced to overlapping historical drivers. First, the area has long been a frontier zone where central state authority is weak and local power is negotiated between armed groups, militias, and cross‑border business interests. This environment created permissive conditions for activities that require territorial shelter from law enforcement, including gambling, trafficking, and informal finance.

A second driver was the relocation of transnational cyber‑fraud operations from Cambodia and Laos beginning around 2019–2021. International media investigations and NGO reports documented how law‑enforcement pressure in Sihanoukville and along the Mekong corridor pushed Chinese‑linked syndicates to seek jurisdictions with even less regulatory scrutiny. Post‑coup Myanmar offered such a vacuum: the 2021 military takeover fractured administrative oversight, diverted state capacity to internal conflict, and reduced international policing cooperation.

Third, the border economy at Myawaddy had already been reshaped by special economic zones and informal enclaves operated through arrangements between local armed actors and business intermediaries. When online scam operations arrived, they could plug into existing security, logistics, and rent‑extraction networks rather than build them from scratch.

By 2022–2023, these factors collectively transformed the Myawaddy corridor into one of the most significant global nodes for industrial‑scale online fraud, with compounds run as vertically integrated enterprises combining recruitment, detention, IT infrastructure, and financial laundering inside single campuses.

Historical Background — How the Scam Compounds Emerged

The rise of scam compounds in and around Myawaddy can be traced to overlapping historical drivers. First, the area has long been a frontier zone where central state authority is weak and local power is negotiated between armed groups, militias, and cross‑border business interests. This environment created permissive conditions for activities that require territorial shelter from law enforcement, including gambling, trafficking, and informal finance.

A second driver was the relocation of transnational cyber‑fraud operations from Cambodia and Laos beginning around 2019–2021. International media investigations and NGO reports documented how law‑enforcement pressure in Sihanoukville and along the Mekong corridor pushed Chinese‑linked syndicates to seek jurisdictions with even less regulatory scrutiny. Post‑coup Myanmar offered such a vacuum: the 2021 military takeover fractured administrative oversight, diverted state capacity to internal conflict, and reduced international policing cooperation.

Third, the border economy at Myawaddy had already been reshaped by special economic zones and informal enclaves operated through arrangements between local armed actors and business intermediaries. When online scam operations arrived, they could plug into existing security, logistics, and rent‑extraction networks rather than build them from scratch.

By 2022–2023, these factors collectively transformed the Myawaddy corridor into one of the most significant global nodes for industrial‑scale online fraud, with compounds run as vertically integrated enterprises combining recruitment, detention, IT infrastructure, and financial laundering inside single campuses.

Structure and Governance of Scam Compounds

Physical layout. Most compounds described in media and rights reports share common architectural features: perimeter walls with limited gates, guard towers or camera arrays, dormitory blocks for workers, separate buildings for administrative staff, and dedicated rooms for call operations (“boiler rooms”). Many sites also include canteens, small shops, and medical rooms, allowing operators to keep workers inside for extended periods. Access is controlled through turnstiles, ID badges, and checkpoints.

Operational cells. Inside the call floors, teams are often organized into cells (e.g., 10–30 people) supervised by team leads. Each cell runs a particular fraud playbook—investment romance (“pig‑butchering”), crypto arbitrage scams, e‑commerce refund fraud, or tech-support impersonation. Scripts, CRM-style dashboards, and KPI boards guide daily quotas such as number of first contacts, conversion rates, and average ticket size.

Security and discipline. Reports describe layered security: private guards, some armed; surveillance cameras covering corridors; and restricted movement between buildings. Discipline mechanisms reported include fines, wage deductions, confinement to rooms, and, in severe cases, physical punishment—indicating a coercive environment incompatible with ordinary employment. Passports and phones may be confiscated on arrival, limiting escape or contact with the outside.

Management hierarchy. Compounds typically feature a multi-tier structure: investor/owner group; site managers; floor managers; cell leaders; and technicians handling networking, VoIP, and device logistics. Some compounds outsource recruitment and transport to third-party brokers, while finance handlers manage cash, crypto wallets, and money mules.

Technology stack. Operators rely on leased bandwidth or satellite links, consumer and enterprise routers, VoIP/SMS gateways, remote desktop tools, virtual numbers, and anonymization techniques (device farms, VPNs, proxies). Laptops and phones are often assigned per cell, with strict device tracking.

Trafficking, Recruitment, and Conditions

Recruitment funnels. Many workers are lured through online job ads promising high salaries in customer service, IT support, or crypto trading. Recruiters target neighboring countries as well as distant regions, offering cross-border transport. Fees for placement or travel may be added as “debts,” binding recruits financially.

Transit and handover. Victims commonly report staged journeys: a meeting point in Thailand or another transit country, a border crossing, then transfer to a secured compound. Along the route, phones and passports may be taken “for processing,” preventing withdrawal once conditions become clear.

Coercion and control. After arrival, some workers discover the role involves scamming. If they refuse, they may face threats, debt penalties, forced overtime, or physical abuse. Movement is restricted; external communication is monitored; and attempts to leave may trigger ransom demands to families. These elements align with common indicators of human trafficking and forced labor frameworks.

Work regimes. Shifts can extend 10–14 hours with limited rest days. New recruits undergo script training, social‑engineering practice, and performance tests. Failure to meet quotas can result in punishments or sale/transfer to other compounds, according to survivor testimonies compiled by NGOs and journalists.

Health and welfare. Conditions vary by site, but documented issues include sleep deprivation, stress injuries from repetitive computer work, poor diet, limited medical care, and mental-health strain from coercion and isolation.

Economics and Criminal Business Model

Revenue logic. The model prioritizes scale and repeatability. Scripts are optimized to target high-value victims (e.g., retirees with savings, new crypto users). Cells focus on building emotional trust, then escalating to large transfers. Average “ticket sizes” reported in case studies range widely, but operators emphasize upselling victims through staged investment platforms.

Cost centers. Major expenses include compound security, IT/networking, recruitment and transport, bribes or protection payments in certain jurisdictions (as alleged in some reports), and laundering fees. Because labor is controlled and turnover is enforced, wage costs may be suppressed relative to revenues.

Payment and laundering. Funds may move through layered channels: bank transfers to front companies, e‑wallets, crypto exchanges, OTC brokers, and money‑mule networks. Some operations favor crypto for speed and cross‑border liquidity, then convert to cash or assets. Chargeback‑resistant methods are preferred once victims are “deep in.”

Integration with local economies. Compounds purchase food, construction, and services locally, and some invest in real estate or hospitality, creating mixed incentives for nearby stakeholders. However, net effects on legitimate trade are negative due to reputational damage and cross‑border enforcement pressure.

Responses and Countermeasures

Law‑enforcement actions. Authorities in Thailand and Myanmar have periodically announced raids, arrests, and deportations related to scam centers and trafficking. Cross‑border tasking has included rescue of foreign nationals and seizures of equipment. Outcomes vary with local security conditions.

Telecom and platform actions. Telecommunications providers and technology companies have announced steps intended to limit misuse—such as disabling connectivity in suspected compounds, tightening KYC for numbers and SIMs, and cooperating with investigations. Messaging platforms have increased takedowns of accounts linked to romance‑investment scams and impersonation.

Diplomatic and NGO engagement. Foreign embassies, UN agencies, and NGOs have documented survivor accounts, assisted repatriation, and urged stronger protections. Public awareness campaigns now educate potential victims about scripted scam tactics and red flags.

Challenges. Enforcement faces obstacles: fragmented authority in conflict zones, rapid relocation of operations, cross‑border jurisdiction limits, and constant script evolution. Without sustained coordination and protection for whistleblowers and victims, shuttered sites may reappear elsewhere.

Allegations, Accountability, and Attribution (A2 framing)

This section follows an attribution‑only approach. Where connections between political, business, or armed actors and scam compounds are discussed in public reporting, they are presented as allegations by external sources, not established facts of this article.

Protection arrangements. Investigative journalism and rights reports have alleged that certain compounds operate with tacit protection from local power brokers, including militia elements or officials who benefit from rents or bribes. The degree and level of such protection, if any, varies by source and case and is often disputed.

Links to national leadership. Some international reports and commentary have alleged that senior figures or their networks may indirectly benefit from the broader illicit economy through intermediaries. These claims are contested and difficult to verify independently, especially in conflict‑affected areas with limited access.

Standard of evidence. Allegations cited in media or NGO publications typically rely on survivor testimony, leaked documents, satellite imagery, financial tracing, or expert analysis. Because multiple parties have incentives to obscure involvement, readers should treat single‑source claims cautiously and seek corroboration across reputable outlets.

Accountability pathways. Potential accountability avenues discussed by legal analysts include targeted sanctions against identified operators, anti‑trafficking prosecutions, asset freezes, and cooperation with telecom and fintech firms to shut down infrastructure supporting the scams.

Reader guidance. If this article is published on a public website, it should include clear sourcing, timestamps, and right‑of‑reply procedures. Statements about individuals or entities should be qualified (e.g., “according to X report”) and updated as verifiable information emerges.

Case Studies (Representative, Non‑Identifying)

Case Type A — Relocated compound after enforcement pressure. A site formerly operating in mainland Southeast Asia relocated to the Myawaddy corridor after regional crackdowns. Survivor accounts described an almost turnkey re‑opening: same team leads, same scripts, same KPI boards — suggesting operational continuity.

Case Type B — Mixed‑use economic enclave with internal zoning. A large campus reportedly combined guest housing, dining, gambling rooms, and scam floors in separate blocks. Workers arrived believing they were hired for hospitality roles, then were reassigned to fraud rooms under threat of “debt.”

Case Type C — Sale/transfer of laborers. Multiple testimonies describe workers who asked to quit being re‑sold to another compound rather than released, with ransom demanded for exit.

Scam Tactics and Script Architecture

Pig‑butchering (long‑con trust building). Operators construct months‑long rapport via romance or business mentorship narratives before staging a fake “investment” opportunity. The fraud escalates gradually (seed win → matched deposit → timed withdrawal → lock‑in → loss).

Tech‑support / impersonation. Actors pose as bank staff, delivery firms, or government agencies to induce urgency and extract credentials or payments.

Crypto arbitrage / OTC plays. Victims are told there is a time‑bound price gap across exchanges. Screenshots and dashboards are fabricated to simulate gains.

Social‑graph amplification. Warm leads are recycled; contact books are traded; look‑alike domains and spoofed profiles reinforce credibility.

Victim Support and Reporting Pathways

Immediate actions for potential victims. Stop transfers; document chats and addresses; alert bank/issuer; freeze accounts; file a police cyber report; warn social contacts exposed to scripts.

For trafficked workers. NGOs recommend preserving evidence (photos, timelines, IDs of handlers) when safe; contacting embassies or hotlines; and using intermediaries to avoid retaliation. Rescue feasibility depends on jurisdiction access.

For platforms/fintech. Evidence bundles with timestamps, hashes, wallet traces, and routing screenshots improve takedown and tracing efficacy.

FAQ (Publish‑Ready)

What is the Myawaddy scam cluster? It refers to a concentration of compounds near the Myanmar–Thailand border where transnational syndicates run large‑scale online fraud operations.

Are the workers voluntary? Many reports document coercion and trafficking: people recruited for legitimate jobs are then confined and forced to scam.

Who are the targets? Victims are global — retirees, crypto entrants, small business owners, or anyone reachable through dating apps, social media, or SMS.

Is this new? The industrial scale expanded after crackdowns in other countries pushed operators to Myanmar’s weaker‑governed border zones.

Is the state involved? Some reports allege protection or complicity; such claims remain attribution‑dependent and contested.

Conclusion

The concentration of scam compounds around Myawaddy emerged from structural permissiveness: contested governance, relocation of syndicates after regional crackdowns, and ready integration into existing rent networks. The result is a vertically integrated criminal economy combining trafficking, fraud engineering, and cross‑border laundering with global victims. Enforcement has disrupted nodes but not the model, which reconstitutes where jurisdiction is weakest. Durable reduction requires simultaneous pressure on recruitment, infrastructure, financial rails, and local protection arrangements — not episodic raids alone.

Alleged Links Between Myawaddy Scam Centers and Min Aung Hlaing (Attribution‑Only Framing)

Because these claims carry legal and political sensitivity, this section presents only what has been alleged by external sources, without asserting them as fact.

1) Context of state control post‑2021. After the 2021 military takeover led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, international observers noted that border zones historically governed through hybrid arrangements (state + militia + business) became even more opaque. Analysts argue this opacity created an enabling environment for illicit economies to expand.

2) Allegations of protection rents. Investigative reporting by international media and rights organizations has alleged that certain scam compounds are able to operate because protection payments or informal understandings exist with power structures aligned with or tolerated by the military authorities. These reports do not claim direct documented orders from Min Aung Hlaing himself, but allege the system of military rule enables or tolerates such protection networks beneath it.

3) Allegations of indirect benefit. Some commentaries have alleged that senior figures could indirectly benefit from the broader illicit economy through intermediaries — via taxation, rents, militia partnerships, or informal tribute structures. These remain allegations without public judicial findings.

4) Military denials and contestation. State‑aligned outlets and officials have rejected claims that the military leadership benefits from or protects scam operations, emphasizing published raids and enforcement actions. They frame the crackdown as evidence of non‑complicity.

5) Evidentiary posture. Because compounds operate in zones closed to free investigation, claims are often based on survivor testimony, leaked chat logs, satellite imagery, and financial traces — all of which can support allegations but rarely meet courtroom evidentiary thresholds without access to actors and books.

6) Analytical bottom line (A2 standard). Under an attribution‑only standard, the strongest statement supported by available open‑source material is: Multiple credible external reports have alleged tolerance or protection of scam compounds within systems under military rule; these allegations are disputed by state actors, and independent verification is constrained by access limits.