Myanmar Satellite Data Reveal Rare Earth Mining Deforestation

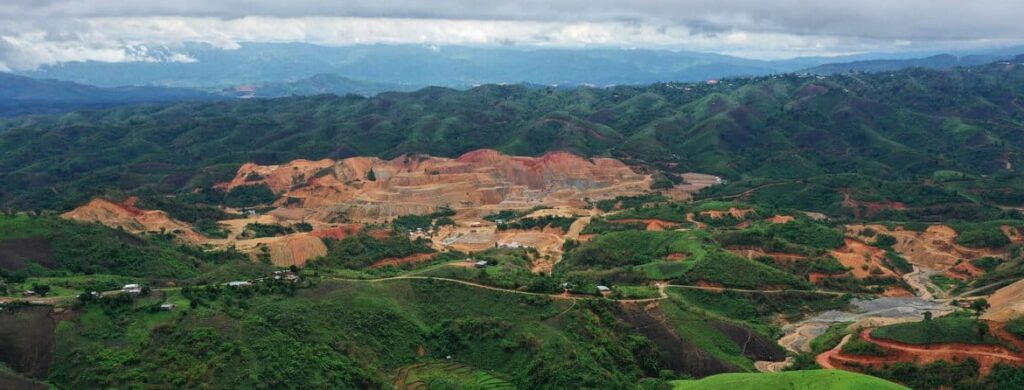

Myanmar’s Kachin state, near the border with China, is a global hub for rare earth minerals. But the dearth of regulations over mining these resources has come at a steep cost to the area’s subtropical and moist forests, according to researchers and satellite imagery collected by Mongabay. Civil society sources in the region, who requested anonymity due to security concerns in the warring country, say mining activities are also causing alarming impacts on human health, women, soil and rivers.

A spokesperson from a local organization in Myanmar told Mongabay that mining in Chipwi and Momauk townships, where much of the state’s rare earth mining is concentrated, increased rapidly in late 2021, the year the coup d’état and civil war began. This was “especially in areas under informal control or lacking proper environmental oversight,” the spokesperson said. Bhamo is another township where rare earth mining is taking place.

“There has [also] been a noticeable rise in deforestation since around 2018, with sharp increases particularly around mining zones due to road construction, land clearing for extraction activities, and widespread tree cutting for fuelwood or to dry the rare earth sludge,” the spokesperson told Mongabay by text message.

From 2018 to 2024, Chipwi, Momauk and Bhamo lost about 32,720 hectares (80,850 acres) of tree cover, according to data from Global Forest Watch. Momauk saw the highest loss, with 12,100 hectares (about 30,000 acres).

Mining has since slowed down or been suspended in some places after the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), whose armed wing is involved in the civil war against the military junta, took control of mining sites from a junta-aligned militia in October 2024, according to sources of Global Witness, an investigative and campaigning NGO. The KIO is renegotiating terms with Chinese companies and authorities that import the elements, while also formulating regulations for rare earth mining.

“The extent to which these will be comprehensive, transparent, enforceable, and in line with international standards remains to be seen,” said Clare Hammond, transition minerals investigations lead at Global Witness.

The KIO has policies and regulations in place and has attempted to introduce basic environmental guidelines, as well as conduct monitoring, the civil society spokesperson said. However, enforcement remains limited, as economic pressures, particularly those related to supporting military needs, take priority.

Patrick Meehan, a lecturer at the University of Manchester in the U.K., co-authored a report on the impact of rare earth mining in Kachin state. He said deforestation in the eastern townships is primarily driven by land clearing for mining operations and the harvesting of firewood, which is used to heat the rare earth sediments to oxides for export.

“Although the areas around Chipwi [and] Pang War [a town] in Kachin state, had already been heavily logged due to agricultural concessions for rubber, banana and sugarcane plantations, rare earth mining is the latest kind of resource boom leading to massive tree cover loss,” Meehan said.

A report by the NGO Myanmar Witness also suggests that a sharp increase in natural hazards such as flooding and landslides may be linked to the rise in deforestation around Pang War, which lies within Chipwi township. The authors reported a significant expansion in the mining area, which grew from approximately 26,000 hectares in April 2018 to 46,700 hectares in April 2024 (from about 64,200 to 115,400 acres). By the end of 2024, they identified nearly 400 rare earth mining sites across Kachin state.

Located near the Chinese border, Myanmar’s Kachin and Shan states hold massive deposits of rare earth elements, including terbium and dysprosium. Most of the mining and processing is done by local residents and Chinese firms, which then export them to China, which controls nearly 90% of the world’s rare earth refining capacity. China’s imports of heavy rare earth oxides from Myanmar rose from 19,500 tons in 2021 to 41,700 tons in 2023, with the trade value in 2023 reaching a record $1.4 billion, according to a Global Witness report.

While Meehan said precise data on the total volume of rare earths extracted from the country is unavailable, Global Witness has documented that all elements extracted from Kachin state end up exclusively at rare earth processors and on to magnet manufacturers in China.

“From here, they find their way to predominantly electric vehicle and wind turbine firms — some of which are household names,” Hammond said. “Permanent magnets are also used in the defense industry.”

Research by a Chinese customs official suggests China Southern Rare Earth Group imports and processes most of its raw materials from Myanmar. Key permanent magnet manufacturers like JL Mag source from China Southern and supply some of the world’s best-known manufacturers of high-tech products, including Tesla, BYD, United Automotive Electronic Systems (UAES) and Nidec Corporation. Some companies contacted by Global Witness, including Nidec, publicly distanced themselves from the Myanmar supply chain.

There’s something in the water

“Forest loss and soil erosion are among the most pressing issues in mining-impacted areas,” the civil society spokesperson told Mongabay. “Water contamination from chemical leaching has led to a decline in fish and aquatic species.” They added that while flooding was once rare in Chipwi township, it’s become more frequent since 2019.

“This increase in flooding is likely due to deforestation and soil degradation caused by mining activities,” the spokesperson said.

Local reports suggest that deforestation and large-scale land excavation may have led to land instability, triggering floods and landslides in recent years. In Pang War, the expansion of the mining sites has reportedly caused injuries and deaths.

Meehan said stripping trees from hillsides creates a lot of landslide risk, exacerbated by the pumping of water and chemicals into the hillsides to extract rare earth elements.

The same chemicals are also fueling farmland pollution and water contamination. Local residents have expressed serious concern over hazardous chemical runoff from mining waste flowing directly into the N’Mai Kha River, a tributary of the Irrawaddy River, the country’s longest. This has also elevated arsenic levels in rivers, not just in Myanmar, but also in those running into neighboring Thailand, posing health risks and impacting livelihoods.

By 2024, water and soil samples collected from creeks in Chipwi revealed severe contamination. One sample from a free-flowing creek downstream of mining sites recorded an “ultrahigh degree of contamination” by toxic heavy metals, including arsenic, cadmium, manganese, lead and strontium.

Hammond said local communities in mining areas can no longer use polluted waterways for drinking and fishing.

“In addition to the water pollution and associated health risks, mining workers present a range of health problems such as coughing, numbness, skin conditions, and kidney issues,” she said. “Protective equipment at the rare earth sites is almost nonexistent.”

Women also face unique impacts from the largely unregulated expansion of mining, researchers say. Local female workers often face mistreatment and sexual abuse, on top of health issues. The civil society spokesperson said there have also been cases where women working at mining sites have experienced miscarriages after returning home.

Instability, inflation, rising food prices, and loss of livelihoods due to the war have pushed many rural residents into working at these mining sites, they told Mongabay. Despite being aware of the risks, many are desperate and “feel they have no other choice.”

While working at mining sites, locals face more problems, sources say.

“Growing inequality among site workers, easy access to drugs, and addiction have become more common, resulting in increased abuse, marital, and family problems in the mining areas,” said one local source.

With demand for renewable technology accelerating and demand for rare earth elements expected to triple by 2035, sources say Myanmar’s rare earth industry is likely to increase.

“Supporting local advocacy organizations is more important,” Meehan told Mongabay, “so that when they get a chance to talk with armed groups or mining companies they have a clear set of demands about what can be done to mitigate some of these harms and get these companies to become much more sensitive with their supply chains.”

👉 “According to Global Witness , rare earth mining in Myanmar is fueling environmental damage.”

Related posts:

Myanmar Earthquake – A Nation in Crisis Amidst Disaster

Myanmar Earthquake – A Nation in Crisis Amidst Disaster

Myanmar Refugees in Thailand Face Uncertain Future as Aid Decreases

Myanmar Refugees in Thailand Face Uncertain Future as Aid Decreases

MYANMAR’S EXILED GOVERNMENT SLAMMED FOR INERTIA

MYANMAR’S EXILED GOVERNMENT SLAMMED FOR INERTIA

What Makes a Womens Bike Unique and Worth It

What Makes a Womens Bike Unique and Worth It

WORLD BANK: MARCH EARTHQUAKE TO CAUSE 2.5% DECLINE IN MYANMAR’S GDP

WORLD BANK: MARCH EARTHQUAKE TO CAUSE 2.5% DECLINE IN MYANMAR’S GDP

US Removes Myanmar Junta Allies From Sanctions List

US Removes Myanmar Junta Allies From Sanctions List