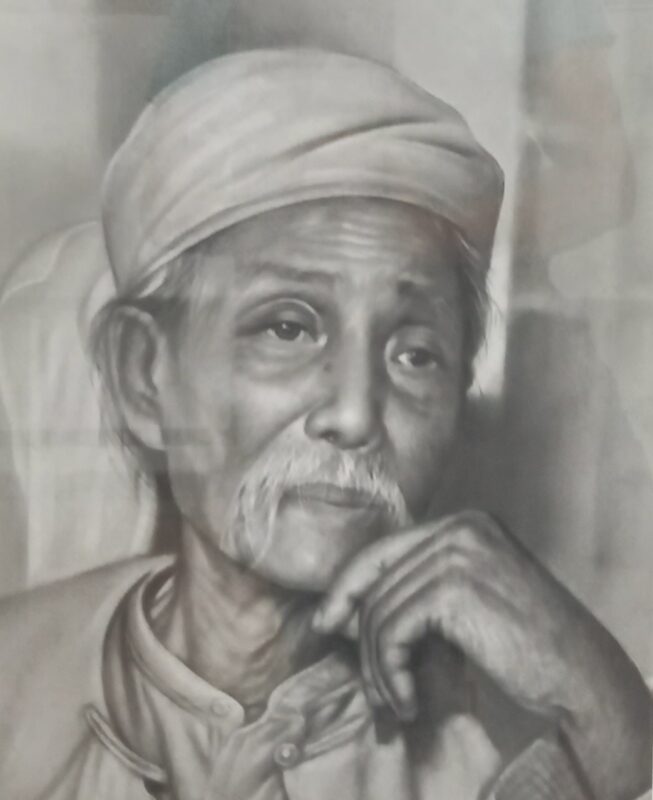

Thakin Kodaw Hmaing — Life, Struggle, and Legacy of a National Conscience

Thakin Kodaw Hmaing (1876–1964), born Maung Lun, stands as one of the most influential intellectuals in Myanmar’s modern history — a rare figure whose pen was as powerful as any rifle in the anti-colonial struggle. He was more than a poet, more than a leader, and more than a historian. He was the mind, the language, and the conscience of a people rising against colonial rule, guiding an entire generation of nationalists with literature, ideology, and moral authority.

In the national memory of Myanmar, he occupies a role comparable to Mahatma Gandhi in India or Sun Yat-sen in China — not through command of armies but through command of moral legitimacy. His words mobilized masses, educated political cadres, and forged unity across ethnic and ideological lines long before bullets and barricades came into play.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Born in 1876 in Wello Village near Ava, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing grew up under the shadow of a fallen kingdom and a rising empire. The Burmese monarchy had collapsed in 1885, and the country entered the British colonial era amid cultural humiliation and political repression. This context shaped him profoundly. From a young age he immersed himself in Burmese classics, Buddhist literature, and political writings from India and Europe. Unlike many nationalist leaders who entered politics through student activism, he entered through cultural guardianship — preserving identity so that politics would later have a soul to defend.

He first gained fame as a playwright and poet. Under pen names such as “Kodaw Hmaing,” he wrote satirical verse, nationalist allegory, and historical commentary in language ordinary people could understand. His mastery of idiom and folk metaphor allowed him to transmit political critique while circumventing British censors.

From Poet to National Leader

By the early 1920s and 1930s, as nationalist agitation swelled, intellectuals and activists looked to him as a moral compass. When the Dobama Asiayone (“We Burmans Association”) emerged — the cradle of modern Burmese nationalism — he became one of its senior leaders. The young nationalists later to be known as the Thakins (including future figures like Aung San and U Nu) studied under his guidance and absorbed his thinking.

His leadership was not administrative but ideological: he provided the vocabulary, slogans, and justifications for resistance. He gave the anti-colonial movement not only a cause but a language of legitimacy — turning political rebellion into a patriotic duty grounded in culture, morality, and collective identity.

Thought, Strategy, and “Moral Militancy”

While many leaders debated armed revolt versus constitutional struggle, Kodaw Hmaing insisted on ideological war first. His belief was simple: a Burmese who does not think like a free person can never fight like a free person. Colonizers, he argued, conquer first in the mind. His essays and speeches trained people to see colonial rule as unnatural, unjust, and defeatable. He opposed violent impulsiveness but supported militant conviction — not pacifism but disciplined nationalism with moral superiority.

He was respected by moderates and radicals alike because he grounded political action in ethical reason, avoiding factionalism. Even after independence, when internal conflicts threatened national unity, leaders across camps continued to cite him as a reference point for national conscience.

Role in the Independence Era and Mentorship of Leaders

By the 1930s and 1940s, as the independence struggle intensified, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing emerged as the elder intellectual statesman of the movement. His home became a meeting ground for young revolutionaries, student leaders, future ministers, and writers seeking clarity and legitimacy for their actions.

He personally advised figures like General Aung San, U Nu, Ba Maw, and other founding actors of Burmese nationalism. Even those who disagreed with him ideologically acknowledged his superior moral authority. He uniquely bridged the world of letters and politics — he was not a man of the gun nor confined to an ivory tower of letters. He was the ethical brain of the nationalist project.

When the Second World War reshaped the political map and Burmese nationalists cooperated with or resisted Japan at different phases, Kodaw Hmaing remained consistent in one principle: independence must not be traded for dependency under a new master. In an era of shifting alliances, his rhetoric preserved the vision of true sovereignty.

After Independence: Mediator, Moral Voice, and Defender of Unity

When independence was achieved in 1948, Myanmar entered a new chapter — but also a turbulent one. Civil wars, ideological splits, communist insurgencies, ethnic rebellions, and struggles for state legitimacy destabilized the young nation. Kodaw Hmaing did not retire as a “victor of the past.” Instead, he dedicated his final decades to preventing national disintegration.

He mediated conflicts between communists and government leaders, urging negotiation over fratricidal war. He warned that the price of liberation should not be a second national self-destruction. Although many politicians of the post-colonial era dismissed moral voices in favor of power politics, few dared openly contradict him — his reputation made him untouchable in moral stature.

Literary Legacy — A Nation Written Into Existence

If Burmese nationalism had a scripture, much of it flowed from Kodaw Hmaing’s pen. His literary output spans:

Political satires and critiques

Historical poetry

Dramatic allegories

Buddhist-philosophical essays

Commentary on world revolutions through Burmese idiom

He fused Buddhist ethics with modern revolutionary vocabulary — a conceptual bridge that made global anti-colonial thought intelligible and culturally compatible for ordinary Burmese readers. His writings shaped the national imagination more deeply than speeches or treaties.

To this day, his phrases, metaphors, and rhetorical structures are embedded in Burmese political speech. Unlike most writers, his words did not merely describe history — they caused it.

Place in National Memory and Historical Ranking

In Myanmar’s historical hierarchy, Thakin Kodaw Hmaing holds a class of his own — closer to a national “founder of thought” than a partisan actor. He is remembered not just as a nationalist or a literary figure but as a civilizational restorer. His name appears consistently alongside the most revered figures of the struggle:

General Aung San — architect of armed independence

U Nu — architect of parliamentary leadership

Thakin Kodaw Hmaing — architect of national consciousness

He died in 1964, but unlike most political figures whose relevance declines after death, his work continues to define the intellectual DNA of Burmese political identity.

Related Profiles (Internal Links Placement)

(These would link to existing or future Myanmar.com profiles)

General Aung San — Father of Independence

U Nu — First Prime Minister of the Union of Burma

Thakin Ba Maw — First Head of State before Independence

Thakin Than Tun — Communist leader and contemporary rival

Aung San Suu Kyi — Heir of the nationalist tradition

AIOSEO-STYLE FAQ (for rich results)

Q1: Who was Thakin Kodaw Hmaing?

Thakin Kodaw Hmaing was a leading nationalist, poet, and political thinker who shaped Myanmar’s anti-colonial struggle and mentored a generation of independence leaders.

Q2: Why is he important in Myanmar’s history?

He provided the ideological and ethical foundation of the nationalist movement, influencing figures like Aung San and U Nu, and helped unify diverse resistance groups.

Q3: Was Thakin Kodaw Hmaing involved in armed resistance?

He did not take up arms himself; instead, he guided the movement through political ideology, literature, and moral leadership, shaping strategy and public support.

Q4: What was his contribution to Burmese literature?

He revolutionized political writing in Burmese, using poetry, satire, allegory, and Buddhist moral language to mobilize the public against colonial rule.

Q5: Did he remain active after Myanmar gained independence?

Yes. He dedicated his later years to mediating post-independence conflicts and preventing national fragmentation, becoming a moral guardian of national unity.

Q6: What is Thakin Kodaw Hmaing’s lasting legacy?

His writings and ideas continue to influence Myanmar’s political culture, national identity, and public rhetoric, securing his place as a foundational thinker of modern Myanmar.